Present at the Revolution

Barry Strauss, ‘Present at the Revolution‘, City Journal, January 18, 2013

______

[Discussing “Rome’s Last Citizen: The Life and Legacy of Cato, Mortal Enemy of Caesar” by Rob Goodman and Jimmy Soni (Thomas Dunne, 384 pp.)]

[Discussing “Rome’s Last Citizen: The Life and Legacy of Cato, Mortal Enemy of Caesar” by Rob Goodman and Jimmy Soni (Thomas Dunne, 384 pp.)]

An obscure suicide from antiquity played a big role in our nation’s independence. The American Revolution’s success depended, of course, on the steely determination of George Washington’s men, freezing in Valley Forge during the winter of 1777–78. But their endurance took at least part of its inspiration from the iron will of Cato, a Roman who ripped open his belly and bled to death in North Africa in 46 BC rather than beg Julius Caesar’s pardon. Indeed, Cato was a hero to Washington, who had Joseph Addison’s famous 1713 play, Cato, performed for his men at Valley Forge. By then, centuries of mythmaking had transformed Cato from a suicidal martyr into a hero of liberty.

Addison’s play argued for death in defense of liberty. A decade later, John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon’s Cato’s Letters went even further and offered a general theory: Liberty was a natural right, embodied in limited government, protected by opposition to tyranny, and characterized by freedom of speech and religion and private-property rights. Originally published in a London newspaper in the 1720s, Cato’s Letters—actually a series of essays that the authors wrote under a “Cato” pseudonym— eventually appeared in book form. The essays had enormous influence on the American Founders and on the writing of the Declaration of Independence.

Cato as a Whig and revolutionary is quite a stretch from the historical Cato. What about the reality? In Rome’s Last Citizen, political speechwriters and journalists Rob Goodman and Jimmy Soni offer an excellent introduction. They have done their homework in the classical sources. Their wise and lively book offers two lessons: first, knowing modern politics can yield insight into study of the ancient world; and second, Rome still has lessons to teach us today. The authors’ Rome includes such phenomena as “favor-swapping,” “personality-driven reform,” “a late-night strategy session,” “campaign apparatus,” and “new rules of engagement.” Balancing out these less inspiring features, Rome also offers Cicero’s oratory, Caesar’s Commentaries, and Plutarch’s Lives, among other treasures. Goodman and Soni make particularly good use of Plutarch’s Life of Cato the Younger, our main historical source, though one that requires caution—Plutarch wrote moralizing biography, not history.

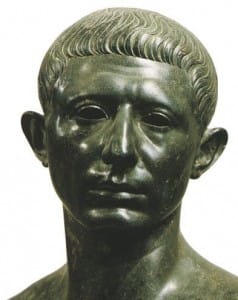

The authors approach Cato with respect and critical distance. They carefully trace a life that took its bearings from a combination of Stoic philosophy and old-fashioned Roman virtue. Marcus Porcius Cato (95–46 BC), the so-called Cato the Younger, came from a prominent family. He followed in the footsteps of his famous great-grandfather, also named Marcus Porcius Cato (234–149 BC) and sometimes referred to as Cato the Elder, who came to symbolize austerity, aggression, and conservatism.

Ancient Rome was a republic: a mixed government combining popular assemblies, powerful magistrates who operated as virtual kings for their year in office, and an aristocratic senate. The Roman republic indirectly inspired America’s constitutional separation of powers. By Cato’s day, though, Rome’s government was out of joint, bitterly divided between populists and oligarchs. Cato emerged as a leader of the second faction. He championed a tiny senate elite’s traditional role of guiding the destiny of the empire and its tens of millions of inhabitants. Yet Cato also defended freedom of speech, constitutional procedure, civic duty and service, honest administration, and the enlightened pursuit of the public interest.

More than anyone else, Cato saw clearly the threat that Julius Caesar posed to the old order. A brilliant and ambitious populist, Caesar wanted to dominate Rome. Unfortunately, Cato made things worse. He turned Caesar into a bigger enemy of the senate than he already was, unintentionally making Caesar stronger. Finally, he drove Caesar into civil war by refusing any compromise. Caesar prevailed, and Cato took his own life rather than admit defeat. His death capped a career of standing up for the republic as he saw it. If there was something blind and wrongheaded about him, there was also something magnificent.

Caesar could not resist joining the debate on Cato’s legacy. Cicero and Marcus Brutus wrote in praise of Cato, while Caesar wrote a pamphlet called Anticato. It was vicious but counterproductive, and it ended up stiffening opposition to Caesar’s rule. While not the main cause of Caesar’s assassination in 44 BC, Cato’s mystique did play a role in the event. He eventually became an icon, cast in different ways over the centuries. The authors trace how Cato the oligarch became Cato the avatar of liberal revolution, from embodying libertas to exemplifying liberty.

Soldiers can take courage from Cato’s example. Politicians should ponder it with care. His life offers a lesson in particular for conservatives about the need for tactical compromise to save what’s best of an old order. For how long should one stand on principle when tectonic shifts rumble below? If only Cato could have read Tomasi di Lampedusa’s 1958 novel, The Leopard, with its cynical but effective lesson: “If we want things to stay as they are, everything has to change.”