Martin Luther King Jr. and Socrates

This week we celebrated the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr., nearly a century after his birth in 1929. Dr. King was the most prominent leader of the civil rights movement, the force that did as much as anything in my lifetime to change America for the better. He was eloquent, far-sighted, and courageous, risking his life many times, as events tragically proved.

Bringing fundamental change to a nation is no easy thing, but King played a central role in doing just that. He was, to use a term coined by James MacGregor Burns and often cited in the scholarly literature, not merely a transactional leader; he was a transformational leader.

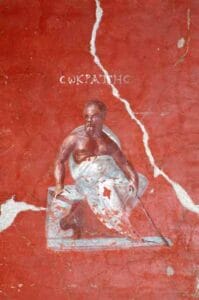

What makes a transformational leader? Wisdom, good judgment, the ability to communicate, foresight, courage, and decisiveness are all requisite. King displayed all those qualities as well as another fundamental characteristic: a sense of mission. In that, he recalls the great religious leaders of history, as he should, because King was a Christian pastor as well as a social activist. But since King spoke to a secular as well as a religious audience, I find myself thinking of a lay leader of the past: Socrates.

King shared something else with Socrates, a sense of mission.

Socrates was a philosopher and an important one. He is no less than one of the founders of the Western tradition of political and moral philosophy. But Socrates was also an active citizen of his country, Athens. He served as an infantryman in the hard fighting of the Peloponnesian War. He stood up in the Athenian Assembly, the democratic legislature in which Athenian citizens participated in one of history’s first direct democracies. There he opposed the clearly illegal motion to try a group of eight Athenian generals en masse, rather than to give them the individual trials that they were entitled to by Athenian law. Socrates courageously tried to stop the angry assemblymen from committing a miscarriage of justice. Unfortunately, he failed. The trial proceeded; the generals were convicted; and six of the eight were executed; the other two were abroad and escaped.

Half a dozen years later it was Socrates’ turn. He stood trial on the grounds of not believing in the gods of the city and of corrupting the young. These were outrageous charges. It was understood by many that they were a smokescreen. The real issue was the anti-democratic coup that followed Athens’ defeat in war. For about a year, a small group of oligarchs imposed a reign of terror on the city, until an armed rebellion by loyal democrats drove them from power and restored democracy. There followed history’s first known amnesty. Aside from the few most guilty parties, no one would be punished for supporting the oligarchy.

Socrates was not one of the oligarchs; indeed, he defied their order to arrest an innocent man. But he was friendly with several of the oligarchs. He was also a well-known critic of democracy. Nor did he play a part in the anti-oligarchic rebellion by the forces of democracy. The amnesty meant that Socrates could not be tried for any of this. The charges of “corrupting the youth” and “not believing in the gods of the city” were a way to get around the law and attack him even so.

The trial of Socrates took place in 399 BC. Semi-fictionalized accounts of his defense speech were written years later by his followers Plato and Xenophon. In his version, Plato makes clear that Socrates believed in his sense of a divine mission. Socrates issues these defiant words to the jury:

“Indeed, gentlemen of the jury, I am far from making a defense now on my own behalf, as might be thought, but on yours, to prevent you from wrongdoing by mistreating the god’s gift to you by condemning me; for if you kill me, you will not easily find another like me. I was attached to this city by the god—though it seems a ridiculous thing to say—as upon a great and noble horse which was somewhat sluggish because of its size and needed to be stirred up by a kind of gadfly. It is to fulfill some such function that I believe the god has placed me in the city. I never cease to rouse each and every one of you, to persuade and reproach you all day long and everywhere I find myself in your company.” (Plato, Apology of Socrates)

Such defiance was not likely to win the jury’s favor, and it did not. Socrates was convicted and condemned to death. Once again, the philosopher stood his ground. Although he had the chance to flee abroad, he remained in prison. He had a responsibility, he said, to his country, for it had nurtured him and provided a bounty of good things. Socrates stayed in Athens and willingly took a dose of hemlock, a fatal poison. He died a martyr to philosophy.

Socrates’ explanation of his decision to stay in Athens, as portrayed in Plato’s Crito, is considered a classic text on civil disobedience. So is King’s famous Letter from Birmingham City Jail, which cites Socrates, among other examples from history. But King shared something else with Socrates, a sense of mission.

Bringing fundamental change to a nation is no easy thing, but King played a central role in doing just that.

We see this clearly in King’s eloquent “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech. In it he speaks of his gratitude to God for allowing him to live in a difficult but inspiring period of history, a period of struggle but also of a human rights revolution. “Only when it is dark enough can you see the stars,” King writes. He goes on to suggest what activists should say to those who were doing them injustice:

“God sent us by here, to say to you that you’re not treating his children right. And we’ve come by here to ask you to make the first item on your agenda fair treatment, where God’s children are concerned.”

King was referring specifically to a strike by sanitation workers in Memphis, Tennessee, where he was speaking, but the words could apply to the civil rights movement generally.

King was referring specifically to a strike by sanitation workers in Memphis, Tennessee, where he was speaking, but the words could apply to the civil rights movement generally.

King’s mighty speech ends on a striking note. He says that, although he would like to enjoy a long life, he wasn’t concerned about that now. “I have been to the mountaintop,” he says. Then he adds:

“I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land!”

The date was April 3, 1968. Tragically, King was murdered a day later.

What makes a leader? The ability to see things that others do not. The capacity to communicate a vision to his followers. The courage to dare. And, in the case of Socrates and King, the conviction that they served a greater power, one for which they would make the supreme sacrifice.

Let’s hope that we have the wisdom to ensure that our leaders never again become martyrs.