Another Date Which Will Live in Infamy

US President Franklin Roosevelt called December 7, 1941 “a date which will live in infamy.” On that day Japan launched its surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. It wasn’t the first December 7 to mark something awful.

US President Franklin Roosevelt called December 7, 1941 “a date which will live in infamy.” On that day Japan launched its surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. It wasn’t the first December 7 to mark something awful.

December 7, 45 B.C. probably found Cicero at his villa on the Bay of Naples outside Puteoli – he was certainly there a little more than a week later. What was on his mind?

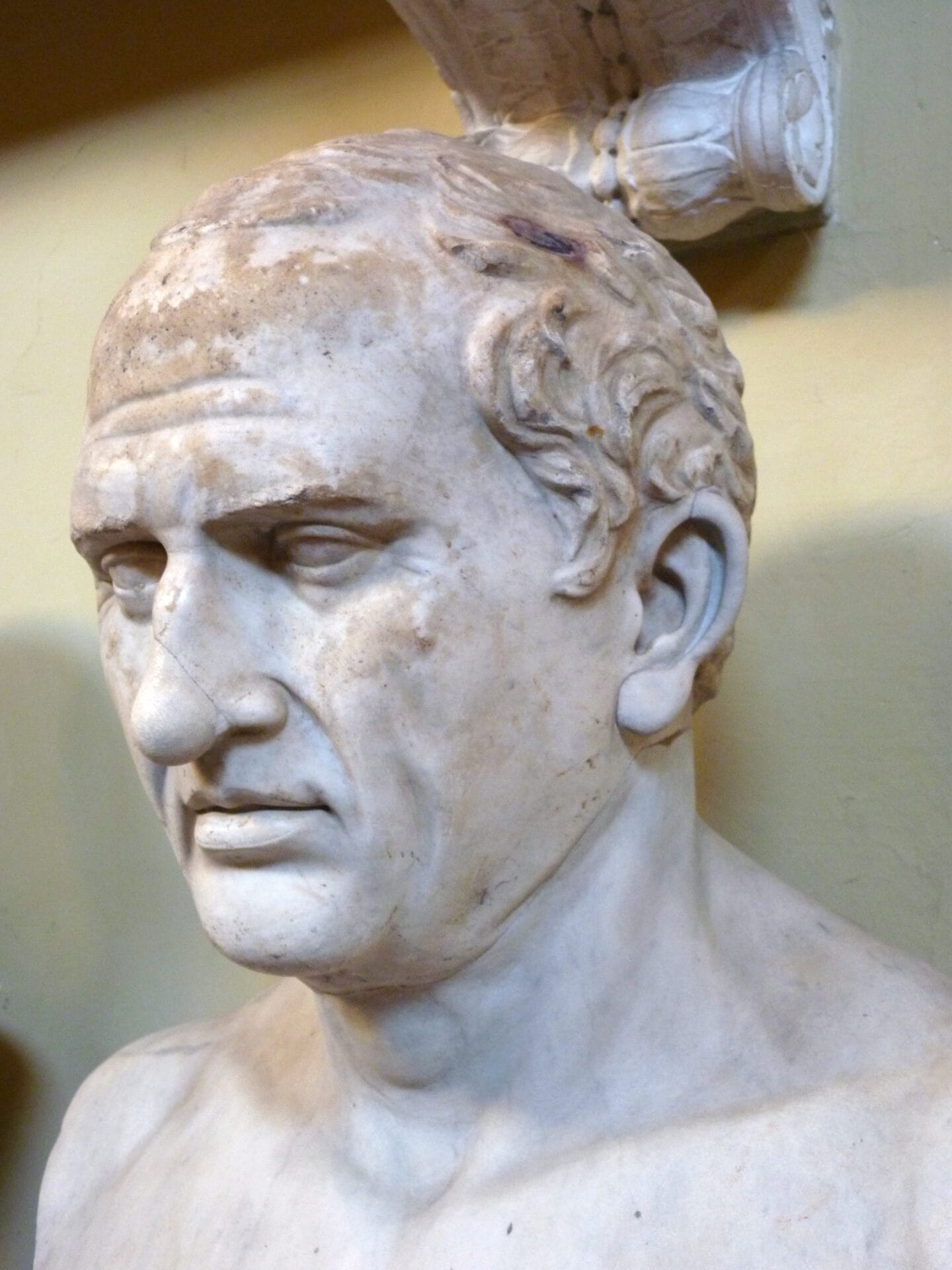

Philosophy, his passion, surely received some attention. But philosophy requires books and Cicero’s most valuable books were missing. A year earlier a trusted slave named Dionysius stole them and ran away. Rumor said that he was now in the Roman province of Illyricum (modern Croatia). Two different governors of Illyricum received letter after letter from Cicero asking them to find Dionysius and his books.

The current governor was a man named Vatinius. He vowed to get Dionysius and he made no bones about wanting something in return. To get the military honors Vatinius craved, he wanted Cicero to lobby the most powerful man in Rome on his behalf – the Dictator, Gaius Julius Caesar. Vatinius had conquered new territory for Rome but then bad weather (he claimed) forced him to retreat. Now he feared that Caesar would block the honors so he asked Cicero for help. And Cicero could help but you didn’t approach Rome’s master lightly.

In his rise to power Caesar first conquered all of Gaul (roughly, France and Belgium. Then, when his political rivals tried to get rid of him, Caesar started invaded Italy and started a civil war. The struggle raged from one end of the Mediterranean to the other. Caesar emerged victorious.

Now the future of the Roman Republic was in doubt. For generations Roman politics had been a boisterous struggle between haves and have-nots, often brutal but open and free. Now Rome was a dictatorship, perhaps a permanent dictatorship, and no one mourned more than Cicero – at least in private. In public, he made his peace with Caesar.

Cicero had the clout to lobby Caesar. Cicero was one of the most famous men in Rome: its greatest orator and philosopher and one of the only political giants to survive the civil war. The Republic was dying, thought Cicero, and death preoccupied him in a year when he lost his beloved daughter Tullia.

The present was gloomy but there was always the past. Maybe Cicero thought back to a day almost exactly eighteen years earlier, December 5, 63 B.C. – the Nones of December according to the Roman calendar. On that day Cicero was consul, the highest-ranking public official in Rome. Rome faced an armed uprising of debtors led by the rogue aristocrat Catiline. On December 5, 63 B.C. Cicero gave the order to execute five of the ringleaders without a trial. That deprived them of their civil rights but, said Cicero, it was necessary to save Rome. People agreed at first but five years later when the threat receded, Cicero was forced into exile as punishment. It took another year before he was able to go home.

What turbulent times Cicero lived in! More was in store. Although Cicero did not know it a conspiracy to kill Caesar was about to rise around him. And that wasn’t all.

On December 7, 45 B.C. there was one thing Cicero could not have imagined. Two years to the day later, on December 7, 43 B.C. he would be murdered. Not just murdered but executed by the official policy of the Rome he loved so well. Shocking as that was, Cicero would have been thunderstruck to know in 45 B.C. that the kid next door would have the power to save him. He was the stepson of the owner of the neighboring villa.

Who was he? How on earth did he get so much power? Why was Cicero killed? Those are stories for another day.

Barry Strauss teaches history and classics at Cornell. He is the author of the forthcoming book, The Death of Caesar: The Story of History’s Most Famous Assassination (Simon & Schuster: March, 2015). You can follow him on Twitter @barrystrauss.