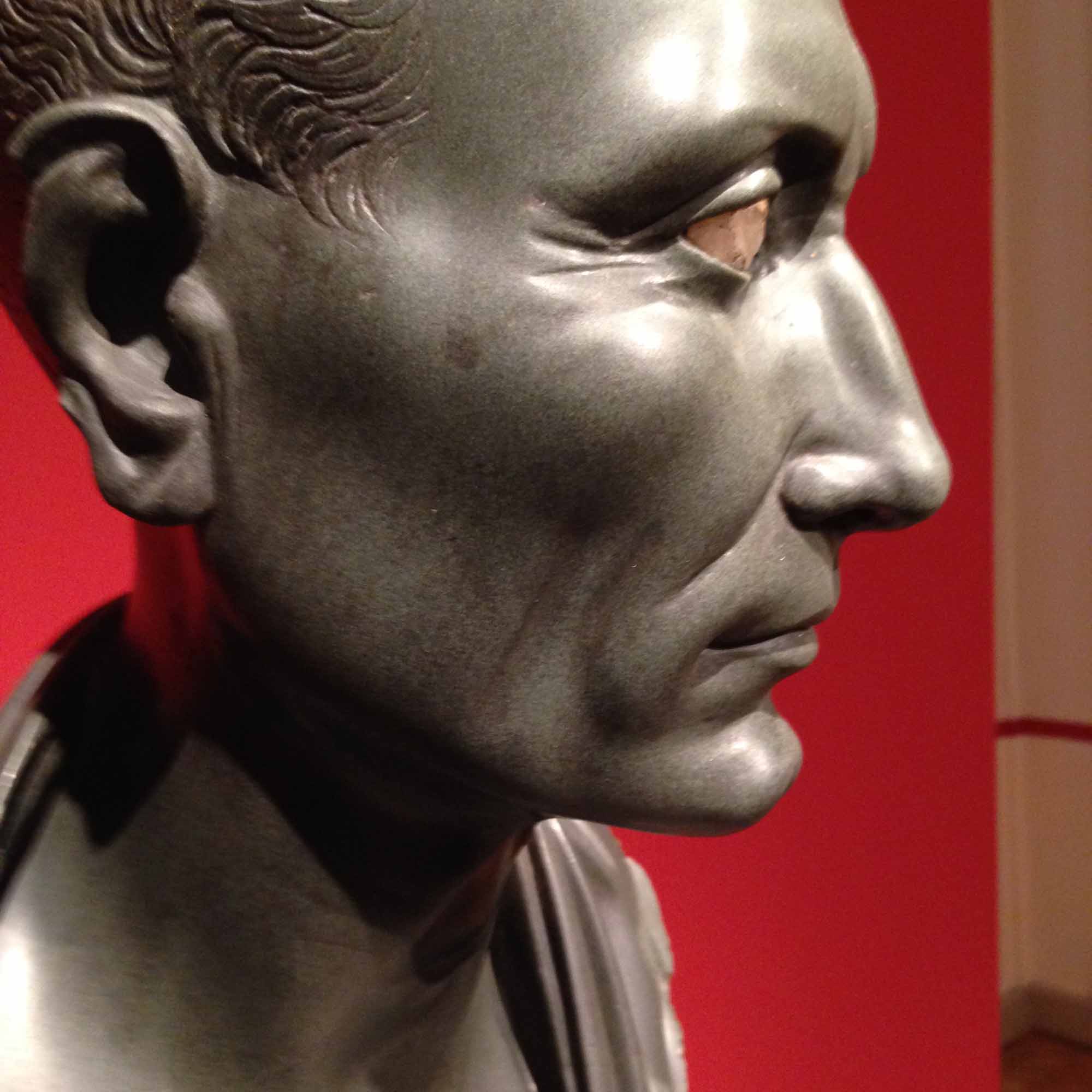

A Lesson in Humble Leadership, from Caesar

Caesar botched his attempt to turn down the throne in his public appearance at the Lupercalia on February 15, 44 B.C. But he did know the value of looking selfless. Five years earlier, when he invaded Italy and set off a civil war, he played the humble leader.

Caesar botched his attempt to turn down the throne in his public appearance at the Lupercalia on February 15, 44 B.C. But he did know the value of looking selfless. Five years earlier, when he invaded Italy and set off a civil war, he played the humble leader.

The Rubicon was a little stream that marked Italy’s northern border. By crossing it in January 49 B.C. Caesar set off a civil war. That’s the origin of our expression, “to cross the Rubicon,” meaning, to make a fateful decision.

Before crossing the stream Caesar addressed his troops. He explained why he was going to war. He fought in defense of the People’s Tribunes, he said. Rome’s ten People’s Tribunes were elected to represent ordinary people and to protect them from abuses by the powerful. Two of those tribunes that year were Caesar’s close friends and they tried to protect his interests in the Senate. Caesar’s enemies in the Senate voted to deprive him of his army, which would have also ended his political career, not to mention his life. The two tribunes used their constitutional right to veto the move, but Caesar’s enemies outflanked them by declaring a state of emergency. The two tribunes fled to Caesar and his army.

Speaking to his soldiers, Caesar championed the tribunes and the rights of the Roman people. He had decided to march on Rome, he said, to take back the government from the faction that had hijacked it. All his life Caesar had stood for the common man and he had street cred when he now branded his enemies as oligarchs.

But that’s not the whole story. After talking about the tribunes Caesar turned to his favorite topic: himself. He accused the Senate of attacking the honor and dignity of the general who had led the troops to victory for nine years in the Gallic Wars – Caesar, of course. Was the army ready to join him and fight for their honor and the tribunes?

They sure were! So they shouted in response. Caesar cleverly connected his men’s honor to his own and wrapped them up in a higher cause – the tribunes and the Roman people. And so, they crossed the Rubicon and unleashed the dogs of war.

There’s a lesson here for leaders. In order to convince followers to lay their career on the line you need to appeal to a higher cause. Make it about “us” and what we stand for, not about “me.” If even a man with Caesar’s swollen ego could do this, then all leaders can.

Barry Strauss is the author of The Death of Caesar: The Story of History’s Most Famous Assassination, available in paperback March 22.